Virtue and vice are inseparable threads in the tapestry of human nature. We are at the same time virtuous and flawed, we sin and seek redemption. Pure virtue can become tedious; excessive vice, unbearable. And we can say as well: virtue can become unbearable; excessive vice, tedious. It is in the back-and-forth between the two—in doubt, guilt, kindness, and desire—where our humanity lies, full of shadows and contradictions.

The exhibition Vice & Virtue, organized by Art Center Sarasota and curated by artist and writer Jessica Todd, delves into this ambiguous terrain—those subtle thresholds where virtue becomes vice and vice becomes virtue. More than fifty artists explore, through paintings, sculptures, photographs, installations, and mixed media works, what it means to be virtuous or vicious in a world of political, cultural, and spiritual transformation.

The artworks (whether figurative or abstract) approach the theme from diverse angles. Some are explicit, like “Fatal Attraction” by John Gallo: a scene in which onlookers use their phones to photograph a crime, turning it into spectacle for social media. Others are more abstract, like “The Shop” by Cortney McNamara, a wooden box with rusty nails and the artist’s own blood. At once seductive and threatening, the piece functions like a trap, a critique of a world where life experiences are mediated by commercial transaction: we buy in order to try to feel something.

In “Sinner Paradise”, a photograph by Loretta Bernardinelli, a roadside motel sign bears a title that seems contradictory—paradise and sin in the same place. Do vices lead us to pleasure? Could paradise also be the setting for sin? The image suggests that both coexist, and perhaps the punishment isn’t the sin itself, but the “no vacancy” sign that bars our entry to pleasure.

A similar question arises in “Bound by Belief”, a sculpture by Rajini Kanth Reddy. A tree trunk emerges from the ground, its roots bloody beneath the surface, its upper half clean and bathed in light. The piece suggests that belief systems, while offering structure and comfort, can also act as prisons. What we call virtue might be a form of repression; what we call vice, a path to liberation.

More contemplative is “A Thoughtful Moment” by the photographer Mark Jarrett. A figure of a woman partially under in water, face hidden under a white hat, suggests a divide between what is visible and what lies beneath. Is virtue what floats above—what is seen? Or is it what is submerged?

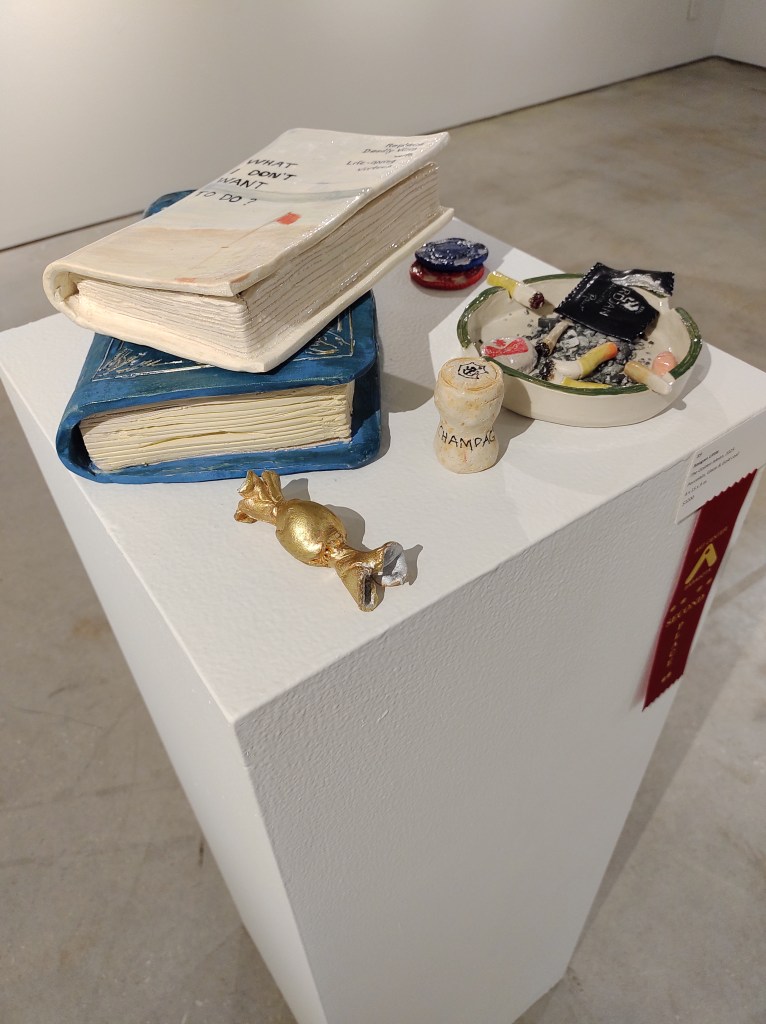

Raegan Little’s porcelain installation, “The Golden Mean”, directly references this unstable balance. On a shelf, socially “vicious” pleasures—books, candy, cigarettes, condoms, a wine cork—invite us to ask: how much is too much? What defines moderation? That fine line is, for many, the boundary between virtue and vice.

At the center of the exhibition is “Antechamber” by Elizabeth Virgilio, a curious and intimate piece. A kind of “shadow box” with lenses allows us to peer into a miniature room: furniture, photographs —a private world glimpsed through voyeurism. The act of looking—of spying—highlights the vice of intrusive observation, the desire to invade what isn’t ours.

Vice & Virtue will be on view through August 2 at Art Center Sarasota, in 707 North Tamiami Trail, Sarasota.

Jesús Miguel Soto

Leave a comment